Last month, I made a couple visits to the Kline Levee. You can read about this big undertaking via our past blog posts.

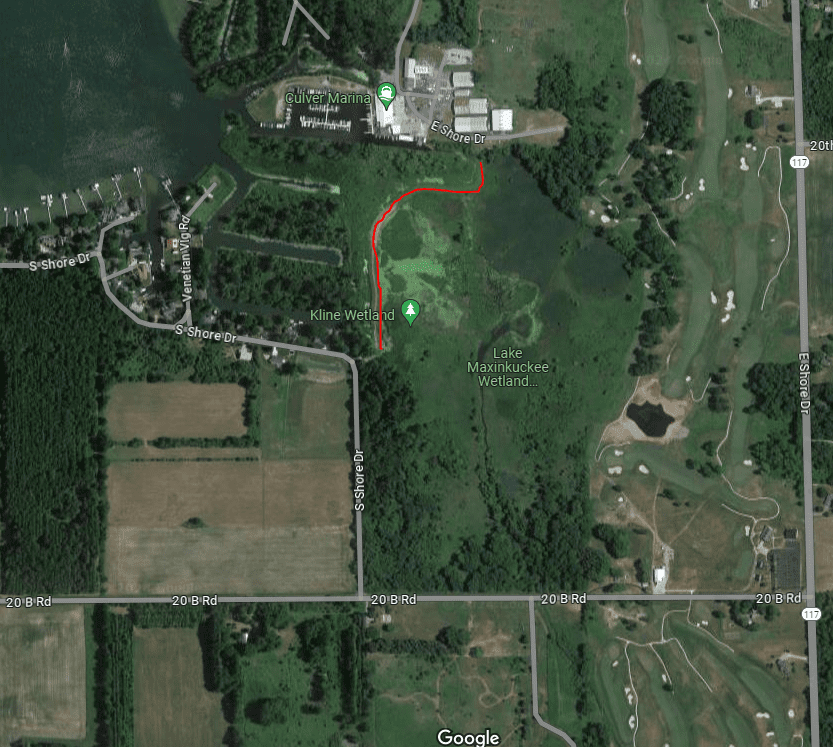

Outlined in red in the picture below, the levee helps maintain an 80 acre DNR wetland complex. This is the final pitstop for water that drains from 1,900 acres southeast of the lake. Here it has time to slow down and clean up, while also providing excellent wildlife habitat.

We do regular water sampling at the levee throughout the year, keeping an eye on nutrient levels. I also will take a garden rake to the outflow to break up any blockages. Oh, and there are beavers and muskrats, always insisting on their own type of infrastructure. For all these reasons, it is just good to have eyes on the ground.

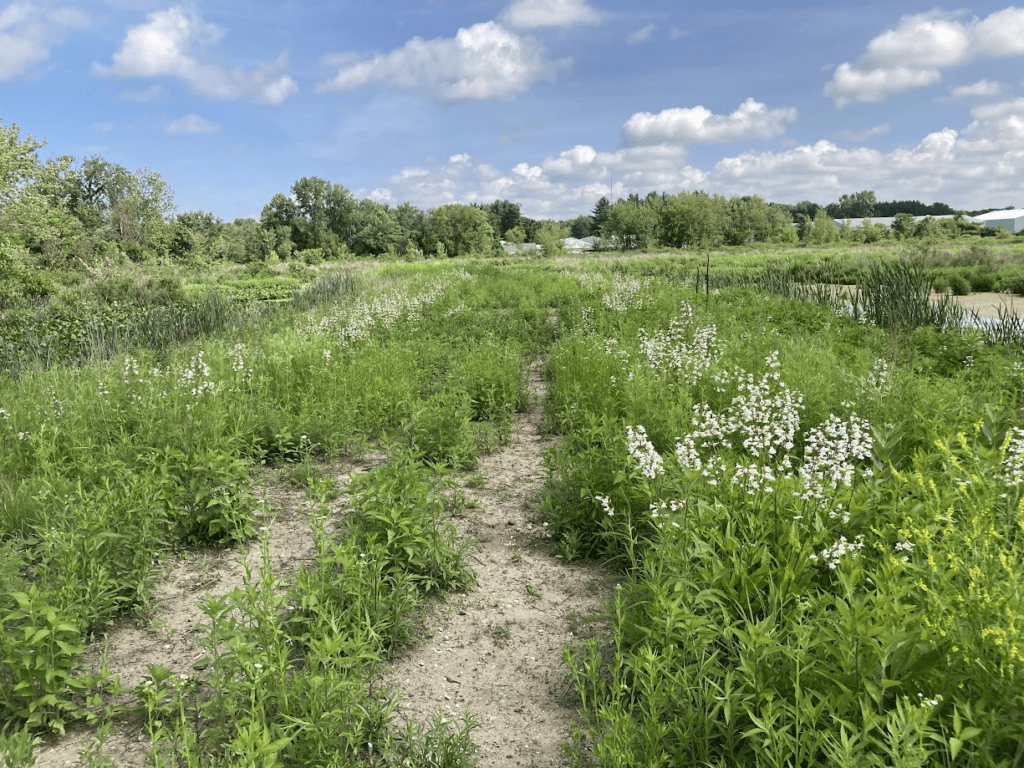

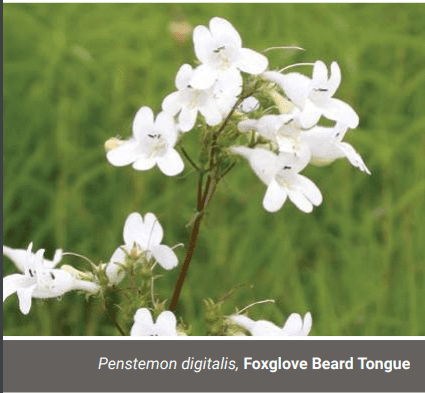

While walking the levee, I was lucky to catch the Penstemon in bloom (white flower below). This was seeded onto the fill after the levee was rebuilt. It’s a wonderful native plant that is a favorite of bumble bees.

I didn’t get a close-up, so here’s a photo from Stantec’s Native Plant nursery, up the road in Walkerton. It never gets old watching the bumble bees crawling all the way inside.

I suppose it’s time to get to the subject of the post though! You’ll soon learn that I’m easily distracted by plants.

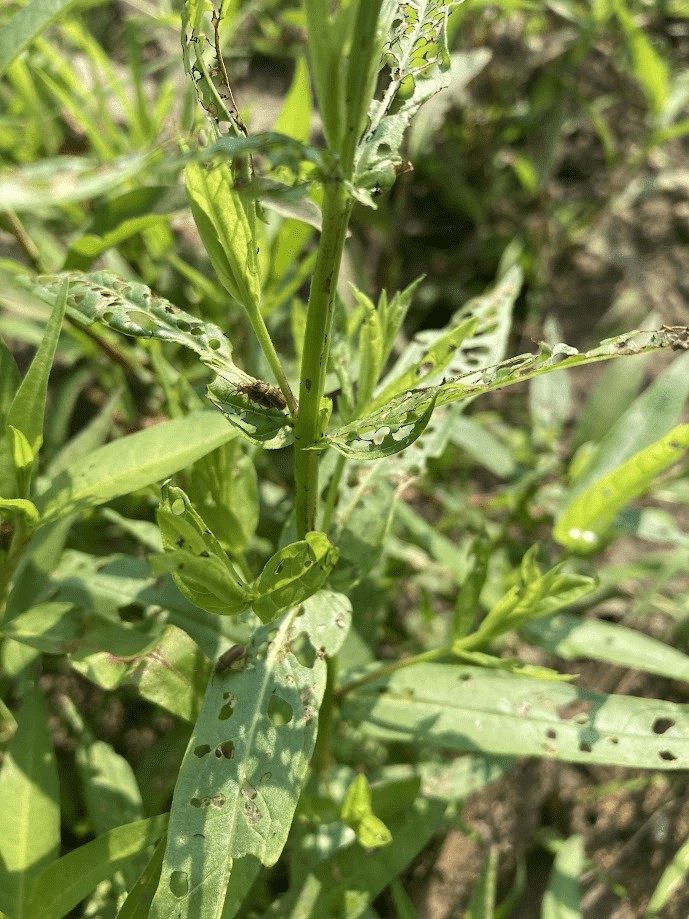

As I was walking around the levee, I found this plant getting pretty heavily munched on by these tiny little beetles… the plant was Purple Loosestrife.

Purple Loosestrife (known to science geeks as Lythrum salicaria) is a persistent invasive plant of Indiana wetlands. This Old World plant – with admittedly beautiful purple blooms – was let loose in the Americas. Now… plant-munching insects will often specialize on consuming one specific plant species or groups of related species. These plants and insects co-evolve, usually over a very long time. There’s a dynamic balance, not too many plants, not too many bugs. So, in the absence of the many pests and pathogens that Purple Loosestrife evolved with back home, there was no check on its growth. It took over precious wetland real estate from the many hundreds of native plant species that evolved in North America.

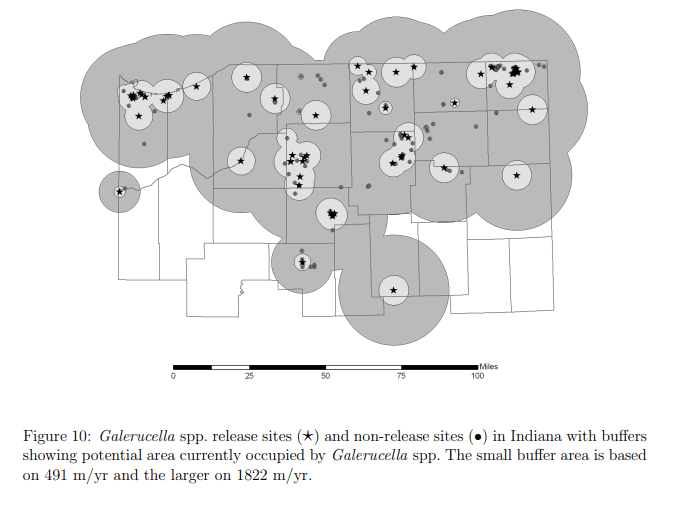

In the 1990’s, scientists and government agencies selected a certain number of these adapted, Old World insect species for introduction into these infested wetlands. A group of beetles known as Galerucella were chosen for release.

transversovittatus, Nanophyes marmoratus) and their impact on Lythrum salicaria (purple loosestrife) in

Indiana” (2012). Master of Environmental Science (MES) Theses. 5.

While researching for this post, I found a 2012 thesis paper from my alma mater, that looks at just this dynamic between the Galerucella and the Loosestrife. You can see Joshua Britton’s fine work here.

I was even happier to find that Lake Maxinkuckee own Wilson Wetland was on the list of studied release sites!

It’s generally considered by practitioners and scientists that the releases, in this case, have done more good than harm. Solid stands of endless Purple Loosestrife were hit very hard by the insects. While the plant was definitely not eradicated, it took a big blow, allowing other plants to again compete for light, space, and nutrients.

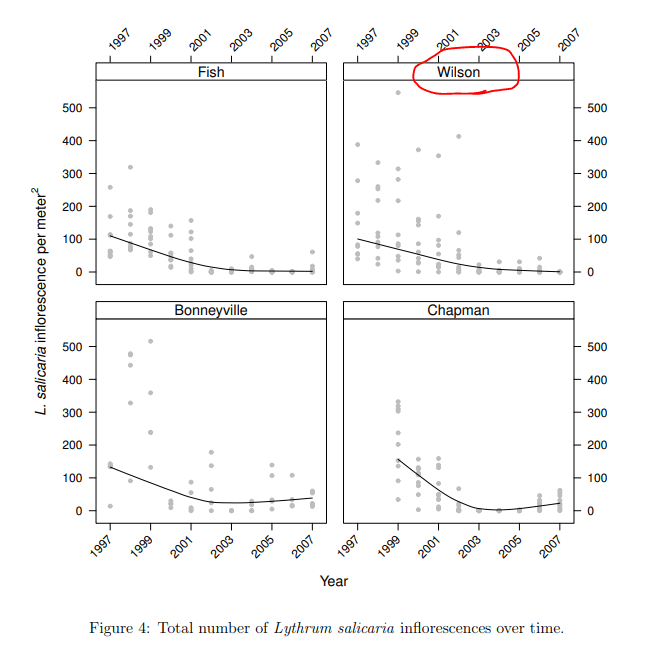

Below is a chart showing the number of Purple Loosestrife flowers per square meter, over time. Over the ten years of sampling that followed the release of the beetles, the density of flowers decreased.

This seems to concur with what I saw at a very high quality, high diversity wetland fen about 8 miles north of Lake Maxinkuckee. While the Purple Loosestrife was still relatively frequent and widespread, each plant was only sending up a single flowering stalk. They were getting chewed on by Galerucella beetles, and there were hundreds of other native species in the mix. It was behaving more like just another native plant that we were used to, and the beetles seem to have formed a self-sustaining population.

Purple Loosestrife is best seen when in flower… I’ll try to take photos in August and September, during its bloom time, to see how abundant it is at the levee.

So, another storybook ending then, right?

Well, mostly.

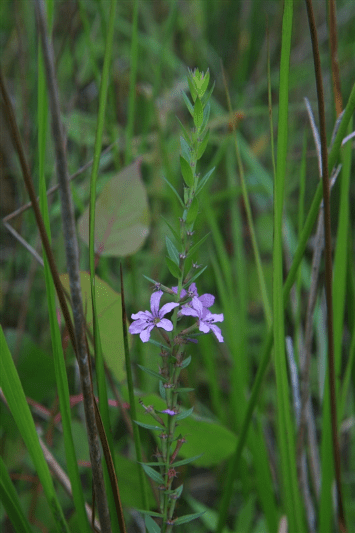

Winged Loosestrife (Lythrum alatum) is a related plant to Purple Loosestrife, except that it is native to North America, not Europe. Winged Loosestrife shares the same genus, Lythrum, with Purple Loosestrife. They have similar DNA and presumably similar biochemistry going on. I have heard from scientists that the Galerucella beetle also chews on this plant, reducing its capacity to compete. To what extent, I’m not entirely sure, but I believe it is considered that this minor disadvantage is still greatly offset by the massive overall gain to the wetland plant communities by reducing Purple Loosestrife.

Photo: A. A. Reznicek, MichiganFlora.net.

It’s important that our interventions don’t create an endless Old Woman Who Swallowed A Fly scenario. As a practice, biological control has matured over the years. But it’s important to carefully weigh and communicate the risks and benefits, as we continue to move species across the globe.

Did I mention I also saw some turtle nests on the levee? Yeah, I’m easily distracted by reptiles as well. But I’ll save that for another post…

Hi, I’m Adam Thada, President of the Lake Maxinkuckee Environmental Fund in Culver, IN. I studied Biology (BS) at Indiana Wesleyan University and Environmental Science (MSci) at Taylor University. The last decade or so has found me in Northern Indiana, working in sustainability, environmental education, and ecological restoration.

Recent Comments