My daughter has a t-shirt that reads: “Science: Because figuring things out is better than making stuff up.” I often like to pair that with another phrase: “Find out before you freak out.” (This last phrase has proven helpful to both the teens and the adults in my household).

Both of these are important reminders when we talk about water quality.

Last year, LMEF was invited by researchers at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas (UNLV), to participate in a nationwide study on the impact of fireworks displays on perchlorate levels in lakes. Perchlorates are chlorine-containing compounds used in the manufacture of explosives like fireworks. According to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), human exposure to high doses of perchlorate can cause thyroid issues. The main sources of exposure are contaminated food and drinking water.

Thanks to the Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA), the EPA is under a court order to develop drinking water standards for perchlorates, which must be based on a thorough review of the best available science on their impact to human health. (As an aside, this is why I think the EPA’s name feels a little misleading. It’s not just about an “environment” that is external to us, nice to care about if we are feeling generous. It’s about the very real health of the physical, human bodies of our loved ones!).

Because there is limited data on the relationship between fireworks use and its impact on drinking water sources, the EPA awarded this grant to UNLV to improve our understanding of perchlorate’s pathways through aquatic systems like lakes and underground aquifers.

Just by mentioning our participation in this study last year, our office received an e-mail, “Is it my understanding that LMEF is against fireworks on the lake?” I had to gently correct the concerned writer, explaining that we were simply trying to observe biochemistry in a systematic way, and that this was not a value judgment for or against certain human behavior. I too have laid out on a blanket with my children, staring up at a night sky bursting with the lights and sounds of fireworks. I have a lot of feelings about those memories. But what the chemistry of fireworks do to produce those amazing colors, and their impact on our air and water, is not a matter of my feelings or opinion, but a matter of measurement.

So let’s take a look at the early results.

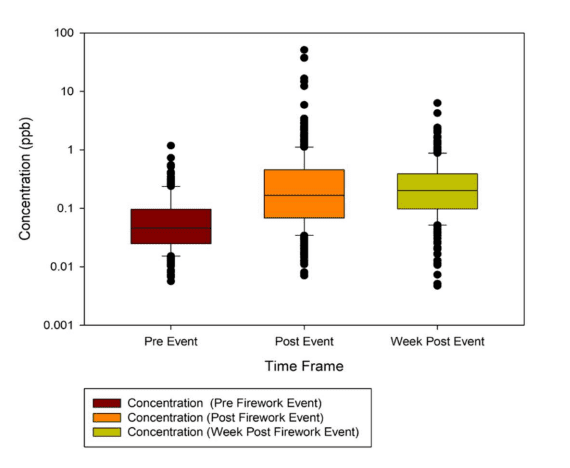

Two hundred and twenty six lakes in 31 states in the U.S. participated last summer. Each was sampled before, the day after, and one week after fireworks displays. Eight percent of samples had perchlorate concentrations exceeding 1.0 part per billion (ppb), and there was a clear increase in concentrations after fireworks.

We took two samples on Lake Maxinkuckee. At site #1, perchlorate levels stayed under 1.0 ppb for all three samples (full results here). At site #2 (full results here), levels hit 1.16 ppb on the day after fireworks, and then declined after one week. Since we had a sampling in the top 8% of concentrations, the researchers asked us last winter if we’d like to participate in a follow-up study. We enthusiastically agreed.

Unfortunately, we received this update in May: “I am sure you have heard in the news about the thousands of grant cancellations in universities… Our grant has been terminated by the federal government… We no longer can financially support the graduate students who helped us.”

The perchlorate study got DOGE’d.

Elon Musk’s Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) made deep cuts into America’s scientific research institutions, terminating many studies already underway, as well as cancelling new ones and laying off staff. It appears that the perchlorate study was caught in the crosshairs.

So, now what?

As of 2017, several states had issued screening values or cleanup goals for perchlorate in drinking water or groundwater. Indiana was set at 15 ppb, while other states ranged from 0.8 to 71 ppb. I’m not a public health expert, but I am a father, so I do have to make prudent decisions for my children with limited information. After seeing a single sample at 1.2 ppb in the lake, I still have no qualms about them swimming in Lake Maxinkuckee, eating fish, or drinking from the Town of Culver public water supply (which isn’t tested for perchlorate). My intuition is that the biggest risk around lakes – by a large margin – is drowning.

While we may have saved a few taxpayer dollars by not funding some scientists-in-training, we do have to pay the real cost of ignorance on this subject. We have made a choice to not learn more about this issue, at least for now, and we have to be honest about that trade off.

Are all these new potential contaminants and toxins getting a little confusing? Are you concerned about microplastics and “forever chemicals” (PFAS)?

Join us at the Culver-Union Township Public Library at 6:45 pm on Thursday, July 24th. I will be sharing an update on the latest state of the science around “Emerging Contaminants” and what they may (or may not) mean for Lake Maxinkuckee.

And remember: “Find out before you freak out.”

Hi, I’m Adam Thada, President of the Lake Maxinkuckee Environmental Fund in Culver, IN. I studied Biology (BS) at Indiana Wesleyan University and Environmental Science (MSci) at Taylor University. The last decade or so has found me in Northern Indiana, working in sustainability, environmental education, and ecological restoration.

Recent Comments