I recently e-mailed the Indiana Department of Natural Resources (DNR) to get some data on Ospreys and Bald Eagles, whose sightings around Lake Maxinkuckee are now common. I quickly received a reply, filled with charts that documented the remarkable comeback story of these flying fish-eaters over the last couple decades.

These and many other birds of prey (raptors) owe a lot to Rachel Carson, a public servant employed by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in the mid-20th century. In her 1962 book Silent Spring, this scientist and advocate meticulously documented how the widespread use of a pesticide called DDT was causing an alarming decline in raptors. DDT accumulated in the tissue of animals, reaching the highest concentrations in raptors, which are perched at the top of the food chain.

Her careful analysis was met with a response we are now quite familiar with, by those who perceived a threat to their revenue streams. Prior to the book’s release, chemical manufacturers threatened to sue her publisher for libel.2 A $25,000 public relations campaign was launched against her. These “merchants of doubt” predicted the collapse of agriculture and widespread famine should we take this woman’s advice. DDT was impossible to live without!

But the compounding environmental crises were simply too severe and obvious to ignore, and in 1970, President Nixon created the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). In 1972, the EPA administrator banned nearly all uses of DDT, except for a few minor applications that lacked alternatives. American entrepreneurs, chemists, farmers, and public servants continued their hard work of innovation, and today the United States produces more food than ever before.

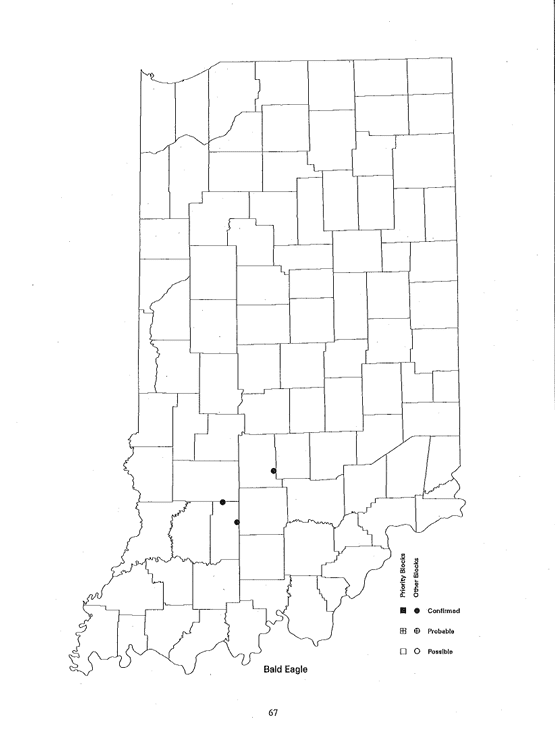

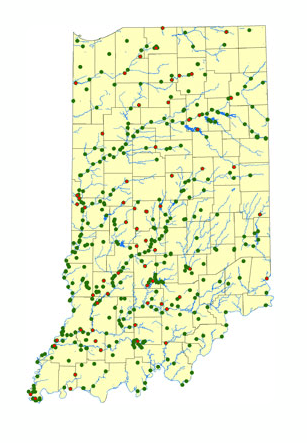

As DDT concentrations in the landscape slowly declined, conservationists got to work. The public funded fish and wildlife departments, which planned for a reintroduction of Bald Eagles, Ospreys, and other raptors to our lands. Non-profit organizations like the Lake Maxinkuckee Environmental Fund erected nesting poles on the shores of our lakes. After an absence of several decades, we once again were treated to the aerial displays of these powerful predators. Indiana now has over 350 breeding pairs of Bald Eagles.3

We need to keep telling these success stories, because I fear that we are starting to take these public agencies and their staff for granted.

While private industry is clearly the best provider for many of the goods and services we need, there’s no profit motive that brings back the creatures that make our lake beautiful, and little incentive to keep our ecosystems healthy. No one makes money by preventing the pollution of our drinking water, which is why we have public officials working hard to learn about PFAS, perchlorates, microplastics, and other new contaminants. The Recycle Depot of Marshall County keeps all manner of nasty chemicals out of our streams and lakes. They are funded by the public. It is easy to forget about a chemical spill that was avoided! But that sort of progress doesn’t happen magically.

I could fill a small tome with all the ways that our lake has benefited from those who have committed their lives to public service. In 2014, we partnered with the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) to complete an investigation of the sediment layers of our lake, providing a crucial snapshot that will be preserved for the future. USGS also maintains a lake level gauge that keeps a history of the lake’s fluctuations. This summer, I called the Indiana Department of Environmental Management (IDEM) to investigate a potential wetland violation, and a field staff was deployed the next day to help the landowner follow the law safeguarding our public waterbodies. Conservation Officers help ensure that we don’t repeat our mistake of unregulated hunting that killed off the elk, deer, turkey, beaver, otter, bear, and wolves from our region. Last and certainly not least, on the shelves in our office sits one of our nation’s best ecological assessments, funded by the public over a century ago. I still use Evermann and Clark’s Lake Maxinkuckee: A Physical and Biological Survey as a research tool. Stop on by to take a look!

Lake Maxinkuckee, like all of Indiana’s public lakes, is held in trust by the State for the benefit of all of the citizens of Indiana. We stand on the shoulders of giants, many who are no longer among us, who used their brief time on earth to responsibly steward these precious gems.

Carson died of cancer in 1964, at the age of 57. She didn’t live to see the creation of the EPA or the DDT ban, much less the incredible resurgence of raptor populations. She embodied the words of Wes Jackson, “If your life’s work can be accomplished in your lifetime, you’re not thinking big enough.”

- Castrale, John S., Edward M. Hopkins, and Charles E. Keller, eds. 1998. Atlas of Breeding Birds of Indiana. Indianapolis, IN: Indiana Department of Natural Resources. 388pp. ↩︎

- https://www.environmentandsociety.org/exhibitions/rachel-carsons-silent-spring/industrial-and-agricultural-interests-fight-back

↩︎ - https://www.facebook.com/INfishandwildlife/posts/pfbid0BAv1Tfg4dfpfJkhZdoN6qum4n2riM1Dq2MZQyTqGCK6QQ4v5ZPFrn2rPCxnY6nFel ↩︎

- https://www.in.gov/dnr/fish-and-wildlife/wildlife-resources/animals/bald-eagle/ ↩︎

Hi, I’m Adam Thada, President of the Lake Maxinkuckee Environmental Fund in Culver, IN. I studied Biology (BS) at Indiana Wesleyan University and Environmental Science (MSci) at Taylor University. The last decade or so has found me in Northern Indiana, working in sustainability, environmental education, and ecological restoration.

Recent Comments